- Log in to post comments

Credit: Julius T. Csotonyi

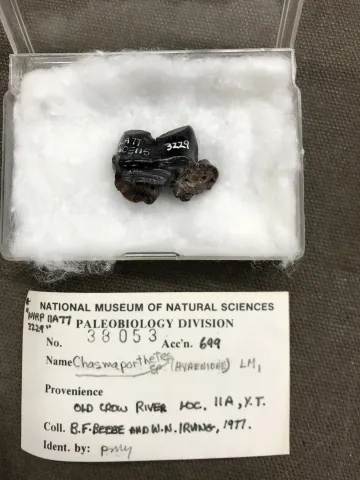

While hyenas living in the Arctic may sound far-fetched, the recent identification of two fossil teeth representing a member of the hyena family from the Old Crow Basin, northern Yukon Territory, proves that it is anything but. These teeth, identified as belonging to the extinct, and so-called “running hyena” Chasmaporthetes cf. C. ossifragus, add further detail to the story of Pleistocene migrations to North America via the Bering Land Bridge. In North America, the furthest north Chasmaporthetes fossils had been found prior to the discovery of the Old Crow teeth was Meade County, Kansas. With about 2,500 miles separating the sites in Yukon and Kansas, this discovery has greatly expanded the known northward range of Chasmaporthetes and are the most northerly fossils of a hyena found to date. Previously, it was thought by scientists that Chasmaporthetes must have crossed the Bering Land Bridge to reach North America, but there was never any solid proof until now. The fossils were originally discovered along the Old Crow River, in northern Yukon, in the 1970’s and had been sitting in storage in the Quaternary Zoology collections at the Canadian Museum of Nature for nearly 40 years. The teeth tentatively identified originally by palaeontologists Dr. Richard Harington and Dr. Brenda Beebe as belonging to the Hyaenid family in the 1980s. However, it was not until Dr. Jack Tseng, a palaeontologist at the University of Buffalo, examined them in 2019 that they were definitively identified the teeth as belonging to genus Chasmaporthetes, which is the only extinct member of the hyena family known to inhabit North America.

Chasmaporthetes dispersed from Asia to North America approximately 5 million years ago and survived until around a 1 to 0.5 million years ago. Present day hyenas are exclusive to Africa, the Middle East, and India, so it may be a surprise to some to hear of them living in the Arctic during the ice age. The teeth representing Chasmaporthetes found near Old Crow may have had special adaptations to survive in the harsh Arctic conditions, such as a thicker fur coat or a coat that changes colours with the seasons, like an Arctic hare.

Along with its Arctic adaptations, Chasmaporthetes also had traits similar to those of the living spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) such as powerful jaws useful for crunching through bone. However, unlike the spotted hyena, Chasmaporthetes also had long, strong legs well suited to running, which lead scientists to refer to them as the “running-hyena”. The combination of long legs and crushing jaws means that while Chasmaporthetes was an accomplished scavenger, it could also successfully hunt other Arctic Pleistocene animals such as caribou and potentially even small bison or juvenile mammoths. With all these potential adaptations, researchers are uncertain as to why Chasmaporthetes went extinct in the Arctic. One theory puts forth that other Pleistocene species, such as the short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) or the extinct bone-cracking dog (Borophagus) may have outcompeted the hyenas for access to prey and carcasses. With the general rarity of fossils from this hyena across its range, including these two recently studied fossil specimens from the Yukon, however, it is difficult to say definitively what drove these animals to extinction.

The results of the study by Dr. Tseng and collaborators Dr. Grant Zazula and Dr. Lars Werdelin have been published in the journal Open Quaternary. The study has also been covered in great detail by mainstream press, such as National Geographic, New York Times, and The Atlantic.